If you wish, you can hear the sermon as it was preached from the UCJ pulpit. Simply click the play button below:

Delivered at the United Church of Jaffrey

June 25th, 2017

Psalm 86:1-10; Genesis 21:8-21

Incline thy ear, O Lord, and answer me,

for I am poor and needy.

Preserve my life, for I am godly;

save thy servant who trusts in thee.

We are gathered, this evening, for a vespers service.

I love the word “vespers.”

The word has a quietness to it.

It sounds a bit like the word “whispers.”

I wonder why I love a word?

Do I love it for its meaning,

or for its sound?

Something about the combination of sound and meaning, perhaps, gives a word a certain mystery.

The word “Vespers” comes from the Greek word Hesperos which refers to the Evening Star.

So Vespers means “evening.”

And, in the Christian tradition, the word vespers refers to the service of worship and prayers that happen in the evening.

Throughout the Christian history, traditions of worship had two centers of development:

In churches, like the one we are in now.

And in monasteries.

The tradition of vespers was part of the “divine offices” – the round of daily prayers that took place during a monk’s daily life in a monastery.

The monks rose at dawn for a prayer service called matins.

Later in the morning prayers were called Lauds.

In midmorning there was Terce

Sext at midday.

None in the middle of the afternoon

Vespers in the evening

And Compline at night.

Some of these “offices” were shorter than others.

But they all involved prayer, and the chanting of psalms.

The monks were very serious about prayer.

While I don’t particularly want to spend my whole life praying, I do admire the thoughtfulness and the discipline of the monastic lifestyle.

And I do think it is meaningful for us, as a community, to have a taste, now and then, of the solemn, quiet practice of vespers.

How does God come to us in the evening?

What whispers do we hear from the divine, as the day grows old,

As the shadows grows,

the sun goes to rest,

And the night falls?

*

Thou art my God; be gracious to me, O Lord,

for to thee do I cry all the day.

Gladden the soul of thy servant,

for to thee, O Lord, do I lift up my soul.

For thou, O Lord, art good and forgiving,

abounding in steadfast love to all who call on thee.

Saint Benedict, who founded a dozen monasteries in and around Rome around 500 AD is, without a doubt, one of the most important figures in the development of Christian worship.

Saint Benedict wrote a collection of rules that gave structure to monastic life.

It was the “Rule of Saint Benedict” that set in place the “round-the-clock” cycle of prayers that I spoke of earlier.

As part of the cycle of daily prayers, Saint Benedict instructed the monks in his monasteries to chant the entire psalter – all 150 psalms – each week. (Wainwright 810)

So in the tradition of Saint Benedict, I have been chanting a psalm.

In this case, Psalm 86.

Thou art my God; be gracious to me, O Lord,

for to thee do I cry all the day.

The biblical scholar Robert Alter has called the psalms the “most urgently personal of all the book of the Bible.” (Alter. The Psalms, p.xiii)

The psalms are never theoretical.

They are emotional.

The psalms are not cautious.

They are unrestrained.

The psalms are written in manner that takes for granted that the person reciting it has a personal relationship with God.

Thou art my God; be gracious to me, O Lord,

for to thee do I cry all the day.

We can safely assume, I think, that when a community of monks spends hours, multiple times a day, every day, reciting the psalms, this personal relationship with God must rub off.

There is a profound relationship being setup here, between the personal and the communal.

Groups of people – monks in monasteries, and people, like us, in churches – get together, in community, to recite something that is deeply personal.

Together we affirm, that each of us, individually, can claim a God-given inheritance – the privilege to speak clearly and meaningfully to the Divine.

*

Judaism

Christianity

And Islam.

According to the Pew Research Center for Religion and Public Life, adherents of these three religions together account for 54.9% of the population of the world, or almost 4 billion people.

All three of these religions – which together represent almost 4 billion believers — trace their origins back to one man.

A single patriarch.

Abraham.

For this reason Judaism, Christianity and Islam are often referred to as “Abrahamic religions.”

And the story that Norma just read for us describes how the jealousies and dysfunctions in one family – Abraham’s family – altered the course of history.

This story that continues to shape the relationship of these religions to this day.

As the Hebrew Bible tells it, God told Abraham that he and his wife Sarah would be the parents of a great people. But this was strange because Sarah could not, it seemed, conceive a child. When, at last, she became too old to bear a child, Sarah, in desperation, instructed Abraham to lie with her maidservant, Hagar, and, in this way, father an heir.

These are the soap-opera like circumstances in which Ishmael, Abraham’s first born son, was born.

But the soap opera was not over. It had just begun, because, against all odds, when she was over 90 years old, Sarah finally conceived and bore a child.

This miraculous child was Isaac.

Sarah, of course, considered Isaac to be Abraham’s true heir, so she immediately told Abraham to send Ishmael and his mother Hagar away.

Hagar and Ishmael had been accepted personages in Abraham’s entourage.

Though a slave, Hagar was the mother of Abraham’s beloved son, Ishmael.

And Ishmael, since his birth, had been Abraham’s hope. His heir. His legacy for the future.

Now, suddenly, and through no fault of their own, the nature of Hagar and Ishmael’s relationship with Abraham flipped from being a source of power in the community, to being the rationale for their exile.

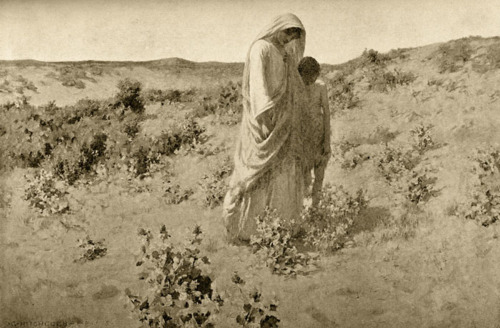

Hagar and Ishmael are given some bread and water, and they are sent into the wilderness.

The water, gone, Hagar places her son in the shadow of a bush and, the text says, rests “about the distance of a bowshot” from him for “she said, “Let me not look upon the death of the child.”

Abandoned in the wilderness.

With no water.

The mother and child face death.

In this, most urgent moment, the text says, “child lifted up his voice and wept.”

One can imagine Ishmael, or his mother Hagar, crying out the words of the Psalm:

Give ear, O Lord, to my prayer;

hearken to my cry of supplication.

In the day of my trouble I call on thee…

*

In the last two months, 114 Iraqi Christians who have been living in Detroit Michigan, have been detained by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency.

ICE has detained these Iraqi’s, claiming that they have criminal records and should, therefore, be deported.

The American Civil Liberties Union filed a suit on behalf of the 114 Iraqi Christians.

Kary Moss, the executive director of the ACLU in Michigan stated that it is…

“illegal to deport the detainees without giving them the opportunity to prove that they could face torture and even death if returned to Iraq.” “Not only is it immoral to send people to a country where they are likely to be violently persecuted, she said, it expressly violates United States and international law and treaties…”

US District Judge Mark Goldsmith temporarily blocked the deportation order, but it is not clear that federal court has jurisdiction in the matter.

The matter is pending.

It is unclear what will happen.

But the Iraqi’s facing deportation have sent a clear message.

Deportation to Iraq would be like being abandoned in the wilderness.

“Deportation,” one of the protest signs says “is a death sentence.”

Protesters rally outside the federal court just before a hearing to consider a class-action lawsuit filed on behalf of Iraqi nationals facing deportation, in Detroit, Michigan, U.S., June 21, 2017. REUTERS/Rebecca Cook

Give ear, O Lord, to my prayer;

hearken to my cry of supplication.

In the day of my trouble I call on thee…

*

God hears Ishmael’s cry in the wilderness.

When Hagar rouses from her stupor, she finds water in the desert.

Ishmael survives to become the father of a great nation.

Muslims believe that the prophet Muhammed is a direct descendant of Ishmael.

But do all stories end so well?

When we cry out in the wilderness…

When we speak the urgent language of the psalms…

Does God always answer us?

If so, how does God answer us?

And what, in all this, is our responsibility.

What does God whisper to us in the evening?

Amen.