If you wish, you can hear this sermon as it was preached in the pulpit of the United Church of Jaffrey. Simply click to the play button below.

Delivered to the United Church of Jaffrey

Jaffrey New Hampshire

El Salvador

To reach the school we climb a gravel track skirted on both sides by tropical undergrowth.

Looping barbed wire and painted cinder block mark the edges of people’s yards.

A chicken scurries in the shadows of the palms.

A small knot of adolescent boys are standing about 20 yards away, at the uphill end of the track.

Joe, who is walking beside me, glances up at the boys. Under his breath he says:

“Now they know we’re here. Nothing happens around here that they don’t immediately know about.”

Joe is the director of International Partners in Mission — the organization that has orchestrated this week long immersion experience in El Salvador.

The “they” that Joe refers to, are the gangs that hold the neighborhoods of San Salvador in an almost uncontested grip of fear.

Before leaving the van, Joe instructed us to stay together and move with purpose. Though our obvious American-ness would protect us from any immediate danger, it would be folly to underestimate the absolute authority that gangs have over these ragged streets.

Vying for territorial control of drug trade, using the threat (and reality) of violence to extort protection, gangs are part of the fabric of daily life here—a far more present form of power than the distant government.

The civil war in El Salvador ended in 1992, but the violence didn’t end — it metastasized into gang violence. By 2015, El Salvador held the dubious honor of having the highest homicide rate in the world at 108 deaths per 100,000 people.

That’s 6656 killings in a population of just over 6 million.

This was the reality that surrounded the school we were visiting.

This was the reality that made it necessary to surround the school with a high fence reinforced with corrugated iron.

As Joe and I returned the gaze of the gang members, the school’s gate opened and we filed in.

Schools of Thought

Dear friends…

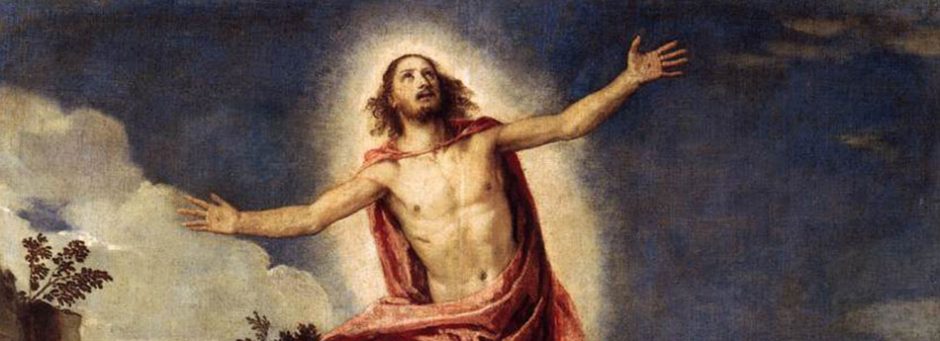

This morning, as you know, is Easter morning!

We have come to the end of Holy Week.

We have gathered, this morning, to celebrate that unusual event.

The resurrection of Jesus Christ!

Now there are, generally speaking, four schools of thought regarding the resurrection of Jesus Christ.

The first of these schools of thought can be called the “It’s a fact” school of thought.

Since we are gathered in a church, this morning, we can assume, I think, that this school of thought may be well represented here.

The “It’s true because it’s a fact” school of thought, holds that the resurrection of Christ is both a divine miracle and a historical fact.

This combination of fact and miracle is considered, by many, to be a strong foundation upon which to build a religious faith.

The second school of thought — that is, I suspect, less well represented here (but perhaps there are one or two of you present) — can be known as the “It’s baloney” school of thought.

Simply stated, this school of thought is the direct opposite of the previous position.

Jesus Christ did not rise again, because people don’t do that, so it is not historical fact, and therefore the whole story is a ridiculous waste of time.

Or, to put it more bluntly, “It’s not true because it’s all baloney.”

If you endorse this view, you are probably here to make your mom happy for once.

Well done!

I applaud your valiant effort. There are few endeavors more worthwhile than making your mother, or better yet, your grandmother, happy.

Try to make a habit of it, will you?

But let’s get back to business…

The third school of thought can be called the “It’s a mystery” school of thought.

This school of thought suggests that we will never know one way or the other, but it acknowledges that there are things about this universe that we simply don’t know, and so, even though it seems implausible, we ought to be willing to go along with it.

I like this school of thought when it makes us think about things. I don’t like it when it makes us stop thinking. The problem with the “It’s a mystery” school of thought is that it can make us throw up our hands and say: “I don’t know, it’s a mystery!”

The fourth school of thought, is the one I am most partial to.. It is can be called the “it’s a metaphor” school…

This school of thought says that Christ’s resurrection may have happened, and it may not have happened, but in the end, the historical fact is not the important thing. The important thing is what the resurrection means to us.

I admit that this is a dangerous school of thought.

“Ugh! the “It’s a fact” people say: “How lame! — how can you call yourself a Christian?”

Meanwhile the “It’s baloney” people think they are vindicated…

“See,” they say, “he said ‘it’s just a metaphor’ — so it didn’t happen! It’s not true. Huh!”

First of all, my dear Baloney people, if any of you are here, I did not say that Christ’s resurrection was “just” a metaphor.

I said it was a metaphor.

To say something is “just” a metaphor, is to suggest that a metaphor is somehow less true than fact.

This is not so.

In our contemporary world, we are told that fact equals truth.

But, if you will forgive me, this is a fairly recent assumption that comes to us from the Enlightenment and the development of the scientific method.

For the vast majority of human history, truth was not communicated as fact.

It was communicated as metaphor.

And this distinction, I believe, is the important point that saves the “It’s a metaphor” school of thought from being lame.

Metaphor points to truth.

I don’t think we should claim to make a decision about the historical fact of the resurrection.

Deciding about it takes away the depth of the mystery, and places it in a neat little academic category that we can safely ignore.

No. Let’s keep the mystery alive in our lives.

The reality that cannot be disputed is that Christ’s resurrection makes a metaphorical claim on us.

Let’s take a challenge…

The challenge is to discover the resurrection in our lives…

Doing this, we find that the metaphorical claim to truth is every bit as strong as a factual claim to truth.

Let me tell the rest of my story.

The Most Vulnerable

El Salvador is a tropical country.

The equator is not far off.

The average temperature in El Salvador is 90 degrees fahrenheit.

This means that schools in El Salvador don’t look like schools in New Hampshire.

Since it never gets cold, there is very little need for walls.

So once we got past the fence, with its corrugated iron barricade, the school opened up before us — a wide, tiled area under a tin roof.

The students — most of whom seemed to be about 5 or 6 years old, were gathered to meet us, and for the next hour, we were treated to a pageant of preschoolers, sitting, standing, swinging, and singing—taking our hands and, in a moment, reducing us to a helpless collection of giggles and smiles.

We went there, eight students from Yale Divinity School, prepared to experience a school in the shadow of fear — and there we were, clumsily singing “Heads, Shoulders, Knees and Toes” in Spanish with tears of joy in our eyes.

For a short time we were mercifully removed from the statistics of homicide.

For a short time, in this circle of small hands, we were gloriously bewildered by our overflowing hearts.

And yet…

And yet…

After the children filed back to their classrooms, the teachers and administrators joined us for lunch.

We followed the precincts of the school as it climbed further up the hill – the distances of the valley stretching away below us.

The sun crossed its noon zenith, and the day was growing hot as we gathered around a long table to eat and converse.

Two of the young women who teach in the school, we learned, live in constant danger.

The gangs know (how could they not know?) that these women offer their children a different reality – a choice that does not inevitably resort to violence.

The fact that these women are still alive may suggest that an ember of hope may burn even within those most invested in gang culture.

The fact that these women come to work each day in spite of the present danger, is evidence that the ember of hope, though small, is strong.

Here, in this place, we are broken open to the tragic certainty that violence and hope are present at the same time, and that this, like the cross, tells of the human condition in its most raw form.

Here, the very real struggle between the immediate threat of violence and the possibility of love, transforms resurrection—an idea we are accustomed to encounter in books or in worship—into a pressing social reality.

While one of the teachers tells us of these things, a child appears at her side. Without interrupting the flow of her words, she leans down and ties the child’s shoelace.

As she looks up from tying the shoelace, Joe translates what she said.

“The most vulnerable,” she said “are also our future.”

The most vulnerable are also our future.

She means the children of course.

To these, the most vulnerable, she gives her life.

But there is something else too – something that brought us to tears when we joined that circle of small hands.

This is something that the children give and are given – something that could so easily be lost, and yet is not.

This is the fine thread of truth upon which the future of El Salvador – and the Reign of God – depends:

the ember of hope that cannot be killed in the streets –

Or on a cross…

that love,

in spite of all,

will prevail.

Amen.