To hear this sermon as preached, please click play below.

Delivered at the United Church of Jaffrey.

July 22nd, 2018

Candelaria

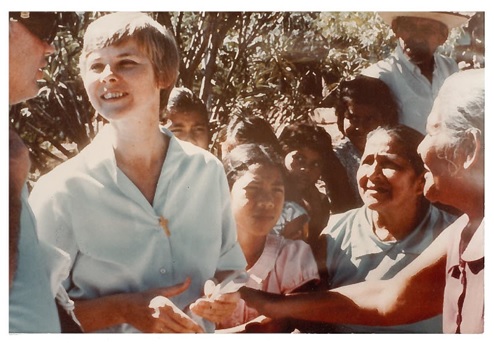

When I was in El Salvador, in 2013, I met a woman named Candelaria.

When I met her, Candelaria, was a short Salvadoran woman in her late fifties, but in 1980 — 33 years earlier — she had been a young the catechist who had been studying under tutelage of Sister Dorothy Kazel — and this first hand connection with Sister Dorothy, was the reason Candelaria was brought to speak to our group of Yale Divinity School students.

On December 2nd, 1980, Sister Dorothy, along with two other nuns, and one lay leader, who was also female — were abducted and murdered by the Salvadoran Army.

All four women were sent to El Salvador by the Catholic Diocese. Sister Kazel herself, was from Cleveland Ohio.

All four of these women were dedicated to working with the poor of El Salvador. Since they were educating the people about their plight, they were seen, by the landowning elite of El Salvador, as a threat.

They knew that they were in danger.

The archbishop of the Salvadoran church — Oscar Romero — had himself been assassinated in March of 1980, but the four women were determined to stay.

After their martyrdom, the four “churchwomen” — as they became known — became important symbols in the Salvadoran struggle for freedom.

When Candelaria spoke to our group, she told us a story about Sister Dorothy.

I would like to begin my sermon, this morning, with that story.

One day Candelaria arrived late, and when she walked in, she found that she was had arrived in the midst a celebration.

Cake had been served.

All the cake, however, was gone.

Seeing Candelaria coming in, and quickly assessing the situation, Sister Dorothy beckoned for her young charge to sit beside her.

When she did as she was told, Sister Dorothy insisted on sharing her piece of cake with Candelaria.

Questioned about the incident later, the nun laughed.

“I learned this from the Salvadoran people,” she said. “Being poor, they are accustomed to share.”

“Being poor, they are accustomed to share.”

I am sure that Candelaria told us this story in order to illustrate Sister Dorothy’s saintly qualities.

But why attention, in this story, is drawn to the Salvadoran people. The story swiftly and elegantly undermined a complex set of assumptions that were operating within me about how people live in poverty.

While one must be careful not to romanticize poverty, neither should one assume that the suffering that results from it necessarily destroys or demeans.

Being “accustomed to share” is a strength that is a necessary response to living with a lack of resources.

Sister Dorothy learned how to share, from the Salvadoran people.

The Salvadoran people, in turn, learned about God’s love, through this generous sister who reflected, back upon them, their own simple generosity.

The cultural encounter allowed these lessons to be learned.

Come Away

You may remember that, a couple of Sundays ago, I preached about the moment when Jesus gave his disciples “authority over unclean spirits” and sent them out, two by two…

I spent most of that Sunday sermon exploring what it meant to follow the instruction that Christ gave his disciples to “take nothing” with them when they went out on their missions.

I bring these matters to your attention because this morning’s lesson, which Bob just read for us, appears to take up where that reading left off.

At the outset of today’s reading, also from the Gospel of Mark, we are told that

The apostles gathered around Jesus, and told him all that they had done and taught.

So…

Jesus gave his disciples a mission.

They accepted the mission, and went out into the world.

And now, they are reporting back.

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

This sequence of events is one we recognize from our own lives.

Students, for example, are given assignments that they go and do, and then they hand in for evaluation.

Employees too, may be given a project by their boss — and when they are done, they are expected to report back on the results or findings.

The sentence we have just heard, suggests that, in this case too, the familiar expectation was at work, and the disciples felt that Jesus was wanted to hear a report of what they had done and achieved.

But this is where the similarity ends.

This is not a quarterly stock holders report.

It is not an annual performance review.

Because none of the details are forthcoming…

Were disciple successful?

We don’t know.

They might have been total failures… but we don’t know,

because the text does not give any of those details.

There are no graphs

No spreadsheets.

We don’t even know if Jesus was pleased or displeased with the report of the disciples.

The text studiously avoids any such data.

All we know, is that Jesus responds by saying…

“Come away to a deserted place all by yourself and rest awhile.”

On several occasions in the gospels, Jesus himself goes off alone to a deserted place.

When he does so, he has a purpose.

He needs to pray.

So when Jesus tells his disciples to “come away to a deserted place” he is making a suggestion that is not only about geographical location.

He is inviting them to pray.

He is inviting us to pray.

Come away,

perhaps,

is another way of saying “Pray with me.”

Sometimes… he seems to be saying … it is necessary to remove oneself from one’s context in order to come commune with God.

Sometimes we must remove ourselves from ourselves, in order to learn about ourselves.

Pilgrim or Tourist

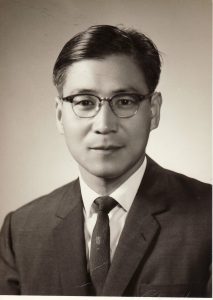

In his book, 50 Meditations, my father, Kosuke Koyama, tells a story about going to the Schwe Dagon Pagoda in Rangoon, Burma.

The story involves two trips to that famous pagoda.

The first time he went to the Pagoda, he observed the proper religious practice, and took off his shoes, and climbed up to the top of the hill where the impressive pagoda sits.

This act of humility — this taking off of shoes — forced him to approach the divine slowly.

“When I took of may shoes, (he wrote) I felt that I was exposed. My modernized and well-protected feet found it hard to walk bare over gravel stones, and heated pavement. The acceptance of all this inconvenience, and in particular of the feeling of being exposed, forms a religious sense of humility and respect.”

My father was reminded of the story of Moses:

“Take off your shoes, for the ground on which you are standing is holy.”

My father was reminded of Jesus Christ:

“In his holy search, the holy God did not go on a motorcycle or by supersonic jet. He became slow, very slow. The crucifixion of Jesus Christ, the son of God, means that God went so slow that he became nailed down in his search for man.”

My father, came away — in this new context — climbing up to a Buddhist Pagoda, he found Moses, and he found Jesus.

Going to the center of another religion, he found his own.

The second time he went to this same pagoda — some years later — he came to find that an elevator had been built for tourists.

Pilgrims took off their shoes and climbed the mountain.

Tourists were still required to take off their shoes — but they could take the elevator.

For the first time in may life (my father writes) I went in an elevator barefooted. My shoes in my hands shouted at me that they must be worn on my feet. While I was feeling the strange sensation of suspension between becoming a pilgrim and becoming a tourist, I reached the top. If I had walked up the hill barefoot I would have been a pilgrim, and if I had kept my shoes on in the elevator, I would have been a tourist. But now I was neither pilgrim nor tourist! A strange sensation of temporary loss of self-identity swept over me.”

An Invitation to Pray

Jesus says “Come away…”

It is an invitation to pray

An invitation to move out of the comfort zone, and pay attention.

To learn new ways — and in the new place, learn also about where you come from.

It is fascinating, and I hope, promising, that this should be the subject of my sermon on the eve of my trip to Indonesia.

While I have gone away

I will remember where I have come from

And I will keep an eye on what I might learn

As a pilgrim, and as a tourist.

Amen.