I had a peculiar experience yesterday.

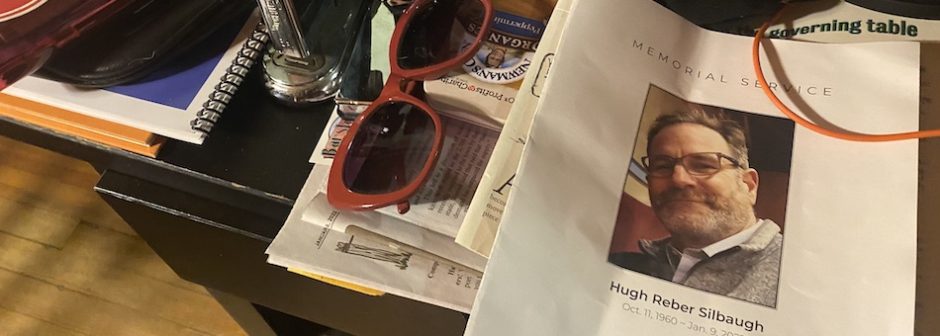

I went to a memorial service, and, instead of officiating over the service, I was down in the pews.

At first I felt uncomfortable.

I’m supposed to be up there, not down here!

I watched, and listened as my friend and colleague, Rev. Lee-Ellen Strawn, the chaplain of Northfield Mount Hermon presided over the service. I recognized what it was like to be her in that moment – intensely aware of being in front of a crowd of people who are in mourning; profoundly aware of the seriousness of the moment; treading carefully lest even the slightest misstep cause concern among those who were bruised and in pain when they arrived. The carefully crafted script; the thoughtful choreography; the rhythm of words and the judicious use of silence… as someone who has presided over many memorial services, I am intimately familiar with all of this.

Rev. Strawn did a lovely job. She was calm. She was serious. She conducted herself with grace and poise.

When it is your job to make insure that the ritual of remembrance is performed well, you must keep your wits about you. You can be sad, but you have to be the steady person in the room – the one who steers the ship back to calm waters.

And it was when I was appreciating her poise, that my attitude about the proceedings changed. I no longer felt the need to be “up there” where I am accustomed to be. I was no longer uncomfortable being down in the pews.

At that moment, I was thankful to Lee-Ellen for being at the helm, because I knew that, in these proceedings, I would not want to have that responsibility.

I was glad to be sitting in the pews yesterday.

It was a lovely day, and the sun came pouring through the windows of the chapel. A couple of rows in front of me, sat a line of students – a group of young women who, until two weeks ago, had been Hugh’s advisees. As Hugh’s son spoke, I shifted my weight a little to let the generous afternoon light bathe my face, and, letting go, I allowed myself the luxury of tears.

A concerned friend recently asked me:

“How do you grieve?”

It was a good question. I had to give it some thought.

Perhaps, because Hugh was not a part of my church, I was free to feel the great pain that his death inflicted on me. I have no convenient professional compartment within which to place his death and understand it.

Minister’s are acquainted with grief, to be sure, but ours is meant to be a professional relationship. The minister’s job is to channel or, maybe, curate grief. We provide grief with a ritualized setting where the community can encounter it graciously – preferably without too much hullabaloo. As such, our role does not allow us to be subject to grief in the same way as everyone else. Sure, we can be appropriately somber, but when it comes to grief itself, I think we are expected to keep it at bay as we would an abstract notion or a particularly well trained dog.

So how does a minister grieve?

The question recalls the other famous vocational conundrums: How does the bus driver go on holiday? Or, How are shoemaker’s children shod?…

Well, we know that the bus driver’s holiday involves a rental car, and the shoemaker’s children go barefoot; and I suppose you have guessed by now that the minister (this one at least) grieves by writing a sermon about grief.

Which is all very well, except that a sermon does not exist solely for the emotional well being of the minister… to succeed, it must have relevance for the spiritual life of the community.

And it wouldn’t hurt to bring our mutual friend Jesus into the proceedings…

Jesus who…

in this morning’s passage from the Gospel of Luke, has begun to make a name for himself teaching in the synagogues of Galilee. The scene set before us today, describes a fraught moment, in a Nazarene synagogue, when Jesus reads from the scroll of the prophet Isaiah, and, in the hearing of all, proclaims himself the fulfillment of the prophecy therein.

If you keep reading beyond where the lectionary passage ends, it quickly becomes clear that this rather audacious stunt doesn’t go over well in Nazareth, and Jesus has to basically hightail it out of town in fear for his life.

But that’s a story for another day…

Today I would like to draw your attention to two things: the prophecy itself and Christ’s claim.

Anyone who has ever listened to Handel’s Messiah, or gone to a Lessons and Carol’s Christmas Eve service, knows that the book of Isaiah is filled with passages that Christians have claimed to be prophecies of Christ. Of all the passages that suggest the appearance of a messiah, observe the one that Jesus chooses to read:

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to bring good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

This is the prophecy that Jesus claims. He unrolls the scroll of Isaiah, and this is what he claims for himself. He reads this job description, points to it and says:

That is me. I am that.

Jesus knows who he is.

He recognizes himself.

He claims his identity with no uncertain terms, before the assembly, and it is from this position of self-knowledge, that he sets forth on his Galilean ministry.

And what is at the core of this prophecy that Christ claims for himself?

He claims that he is the one who “brings good news to the poor… the one that “proclaims the release of captives… He is the one who will give sight to the blind, And bring freedom to the oppressed.

When Christ claims “I am that!” he describes relation.

His I is not “me.” His I is “we.”

Identity, for Jesus, cannot exist without relationship.

To be, in a spiritual sense, is to move at once from “I” to “we.”

I am. We are.

The mystery of the divine character of Jesus has something to do with this: To be God, is to conjugate the verb “to be” and move from the singular to the plural.

God is relational.

When Christ says “I am,” he says “we are.”

Hugh Silbaugh famously described his relationship to teaching in this way. He said that teaching, for him, began as an act of rebellion, grew into an act of love, and ultimately became an act of faith.

I could see the love part, manifestly – and you can see it too, in the quote that I have offered you from his faculty profile. It is my great hope that each of you, who is listening, can recognize this teacher – the teacher who cannot sit still, for love of the subject. The teacher who may have 16 students in the room, but makes you feel like you are the only one there. The teacher who laughs. Pauses. Reads the text lovingly, and reaches, through it, right into you. Hugh was the consummate artist at teaching. When you were in his classroom you felt safe, challenged, supported. You could speak because you knew you were being heard. The seeds of your imagination could grow because he had furrowed the ground, dug in the compost and shown you the sublime beauty of the fertile ground.

I am. We are.

You know a great teacher when you enter her classroom. Her I is not me – her I is we. His teaching does not exist without relation, and the more a teacher can lovingly lean into the “we” of his identity, the more everyone learns – not only about the subject, but about being a compassionate human being.

I learned, yesterday, why Hugh said that teaching began as an act of rebellion. It was because Hugh was enrolled at Harvard Law School, when he came to the realization that, regardless of all the momentum of that trajectory – all the prestige and the promise of success – he did not see himself as a lawyer. That was not who he was. He was not a lawyer.

I am. We are.

He was a teacher.

So he dropped out of Harvard.

We are accustomed to “getting in” to Harvard as the measure of success – but in Hugh’s life, dropping out of Harvard was the crucial, decisive moment – akin to Jesus being chased out of Nazareth. Hugh knew who he was, and that wasn’t it.

His I was not “me”. His I was “we.”

I am. We are.

This is an act of faith, my friends. The best teacher conjugates the verb “to be” with their very life moving from the first person singular to the first person plural.

I am. We are.

This movement is a giving over, entirely, of the self into what is great and true about “we.”

It is easy to think that “we” is a place of mob violence and ethical lapse, as it was, undoubtedly, on January 6th…

But “we” as Jesus taught us, and as Hugh also embodied in his life – is the essential category of faith.

“We” rebels against the imperious and cynical “I” of consumer culture.

“We” is the paradigm shift to love.

“We” is the teacher’s act of faith, sown in the fertile hearts, hands, and mind of beautiful young people, making them (if it is possible) even more beautiful.

Thank you, Hugh.

Good bye.

I am. We are.

Amen.