If you wish, you can hear the sermon as it was preached from the UCJ pulpit. Simply click the play button below:

Delivered at the United Church of Jaffrey

October 1st, 2017

Exodus 17:1-7 | Matthew 21:23-32

The Israelites, have been freed from bondage in Egypt…

But they are complaining!

After everything that God and Moses have done for them – all the plagues of Egypt and pillar of fire and the whole thing with the Red Sea splitting in half…

They’re complaining?

Moses is not going to put up with it…

“Why do you find fault with me?” he says… “Why do you put the Lord to the proof?”

Well, it turns out, the children of Israel actually have a pretty decent reason for belly-aching.

They, and their children, and their livestock, have been making their way through the desert.

And there is no water.

It’s like a Geico Ad: When you wander through a desert, and there is no water, you get thirsty. It’s what you do.

At length, even Moses has to begrudgingly admit that being thirsty is a legitimate gripe, so he asks God for help and God orchestrates a miracle. Moses strikes the rock with his staff, and water pours forth.

When you are dying of thirst, water is the single most important thing.

So one would think that this miracle – this water pouring forth from a stone — would make the children of Israel ecstatic!

But if the children of Israel were pleased, the book of Exodus doesn’t bother letting us know one way or the other.

After the miracle the text simply reports that Moses

called the name of the place Massah and Mer′ibah, because of the faultfinding of the children of Israel, and because they put the Lord to the proof by saying, “Is the Lord among us or not?”

“Is the Lord among us or not?”

This may be the question…

It is the BIG question!

“Is the Lord among us or not?”

This is the question of faith…

It is the question of human history.

In this story from the Book of Exodus, the answer seems to be satisfactorily clear.

The children of Israel were thirsty. Moses produced water from a rock.

The Lord must have been among them.

But what about the times that are not so clear?

Because, after all there are times when people die of thirst.

There are times when the miracle does not happen.

What then?

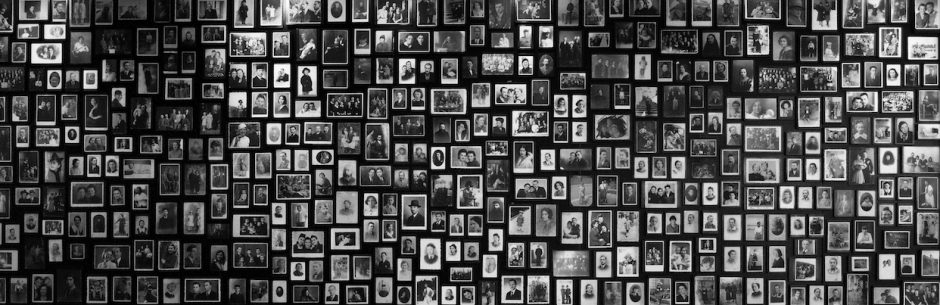

Indeed, the story that we have been considering this morning, is part of the founding narrative of the Jewish people – the very same people who, centuries later, suffered the Holocaust.

In just 4 years – from 1941 to 1945 — the Nazi’s successfully killed 6 million Jews.

The only way to accomplish murder on such an immense scale, was to use industrial methods.

That evil should exist on such as scale as this, threatens our ability to have faith in what is good.

With this historical fact on our hearts, the question from the Book of Exodus gathers a deeper, more troubling significance.

“Is the Lord among us or not?”

*

As Christians, we look not only to Moses for the answer to this question, but also to another Jew – Jesus of Nazareth.

In the second passage that Helen read for us this morning, we find Jesus being tested by the chief priests and the elder in the temple.

“By what authority are you doing these things, and who gave you this authority?” They ask him.

In the temple, the question of authority, was the question. If Jesus could show that he spoke with authority, he would essentially be answering the the BIG question –

Was the LORD with him or not?

But instead of giving them a yes/no answer Jesus retorts with a kind of rhetorical sleight of hand that puts his questioners in an awkward corner.

Jesus then tells the parable of the two sons.

A man who owns a vineyard has two sons. He tells his first son to go to work. The first son refuses, but changes his mind and goes to work. The man tells his second son to go work. The second son says he will work, but doesn’t. Which son “did the will of the father?”

The elders and chief priests say: “The first son.”

And in response to this, Jesus said to them,

“Truly, I say to you, the tax collectors and the harlots go into the kingdom of God before you. For John came to you in the way of righteousness, and you did not believe him, but the tax collectors and the harlots believed him; and even when you saw it, you did not afterward repent and believe him.

In this banter, and in this parable, the question that is at stake is the BIG question: “Is the Lord among us or not?”

But here, the question is framed as a question of authority.

Spiritual authority is given to the person, or persons who God is with.

And for Jesus, God does not obey the rules of human culture. God does not prefer to be with powerful people.

God does not prefer the chief priests.

God is cannot be bought with gold.

God does not take private jets.

No.

For Jesus, God is with the people who are in need.

The people who are in need, and so believe — the thirsty who ask for water in the wilderness.

God is with those who suffer.

God is with those who are on the edges.

The God that Jesus tells us of, is more interested in the flooded out slums of San Juan, than the air-conditioned Oval Office.

*

But if this is so, this makes God’s disappearance from Auschwitz in 1942 all the more troubling.

Many people, not only Jews, have pointed to the Holocaust as the best evidence that there is no God – or, if there is a God, that a God that would allow such a thing to happen cannot be a God worth worshipping.

I agree.

I am a man of faith.

I believe in God.

But I agree, that the historical fact of the Holocaust challenges our faith in God.

Especially, if we are to believe Jesus, and God seeks out those who are in pain – wouldn’t God be more present during the Holocaust than any other time?

Why does it seem as though God was absent at the most crucial hour?

I have heard it said that there is a tradition among some Jews that says that God was on vacation during the holocaust.

On vacation?

That’s not much of an answer.

One Rabbi that I heard speaking on YouTube, when confronted by an angry second generation holocaust survivor, gave the “we just can’t understand God,” answer. It goes like this: God is eternal, and we are finite, and so we cannot know God’s purposes. We may suffer, but our short lives are merely a preparation for eternity. The holocaust was just a part of that larger picture.

This is unsatisfactory to me.

I will not worship such God.

*

I don’t know if there is a satisfactory answer to this problem.

But let us return to The Big Question.

“Is the Lord among us or not?”

I want to focus on the word “among.”

What does it mean to say that God is “among” us?

The proof that the LORD is “among” us – according to the Exodus story that we heard earlier – comes from the show of power.

Miraculous water gushing forth from stone.

Stories like this are not limited to the book of Exodus…

The gospels are filled with such stories.

Jesus cured lepers, made the blind see, fed the multitudes on scraps of food, walked on water, turned water into wine, even raised people from the dead.

There is no lack of miracles that seek to prove that Jesus is divine.

But these stories, I would argue, are not the real reason we believe in the divinity of Jesus.

These miracles are impressive, but as proof that Jesus is God “among” us, they are unsatisfactory.

God was not among us to impress us.

God was not among us to wave a magic wand and remove all suffering from our lives

God was not among us to show sympathy for our plight.

God did these things.

But to me, the evidence that God was truly among us, was the fact that, as Jesus, God did that thing that is most human of all…

God suffered.

*

In his book, Night, Elie Weisel, the author and Auschwitz survivor, tells the story of a boy – a mere child – who was hung at the gallows in front of the entire population of the camp.

As the child was dying, Weisel heard a man behind him utter the question:

“For God’s Sake, where is God?”

“And from within me,” Weisel writes, “I heard a voice answer: “Where He is? This is where—hanging here from this gallows… “

For a Jew, this is a horrible story. It suggests that God is dead.

But for a Christian, this story, though horrible, has a different resonance.

For a Christian, this is a story of God, “among” us.

Dying, God is does not die.

Dying, God lives most intimately among us.

*

This is where my sermon ended last night.

But in the shower this morning, I became aware that in conclusion, I have offered a Christian solution to a Jewish problem.

Are there not Jewish answers that are satisfactory?

For this, I turn briefly, to the work of one of our generation’s great commentators on Religion – our own Bob Abernathy.

In an episode of the Religion and Ethics Newsweekly that was dedicated specifically to the problem of God and the Holocaust, we hear this counterpoint.

A holocaust survivor, Dora Lefkowitz says:

I had one sister and two brothers. I was the oldest and the only survivor of my family. Why? What did they do so terrible that they had to perish? I think if God is so great and so powerful, he could have struck Hitler down before he killed so many Jews. That’s my feeling.

In response to this, Professor Arthur Hertzberg of New York University says:

“That is one of the deep religious responses to the Shoah, to defy God. To take it with indifference is not a religious response. To go and rebuild is a religious response, to defy God is a religious response because that is to take what happened at the utmost seriousness, as a matter of life and death, of your own life and death.”

Jews too, confront death with their religion. They find death, and they find resurrection. Hear these words from Bob Abernathy’s interview with the great Rabbi Jonathan Sacks who said:

No Jew knowing our history can be an optimist, but no Jew worthy of the name ever gave up hope. The story of the Jewish people is the story of the victory of hope over despair and of the spirit over every kind of physical power. We are the people who never gave up hope, and I want to say to you: you needn’t be an optimist, but you must never give up hope, because together we can make a better world.

Amen.