If you wish, you can hear the sermon as it was preached from the UCJ pulpit. Simply click the play button below:

Delivered at the United Church of Jaffrey

June 11th, 2017

Psalm 8; Matthew 28:16-20

The quiet streets behind our house were weary after the long winter.

The quiet streets behind our house were weary after the long winter.

Spring puddles were sulking in the grass and collecting where the road dipped.

My mother held onto my elbow with one hand and used the other to poke at the ground with her cane.

A neighbor was tinkering with something in his driveway.

A year had passed since Dad died.

“You know,” she said, “your father is dead, but he is still with me.”

A chatter of starlings stirred in the underbrush. I didn’t say anything.

We came to the end of the block and as we turned back toward home she said, “this grief is my new way of loving him.”

Somewhere in the woods beyond the houses, some of the neighborhood kids could be heard yelling up at the sky.

*

When I looked over the readings for this morning, that Liz just read for us, I discovered a common element.

Constancy.

The Online oxford dictionary defines constancy as “The quality of being faithful and dependable.”

Constancy, obviously, is related to the word “constant” which, I learned, comes from the Latin word “Constantia” which means “standing firm.”

To become a theological term, though, constancy must suggest more than simply standing firm.

Constancy must involves love.

A faithful, dependable love.

That is what God gives us, and what we try our hardest to give each other.

In Kerrigan’s triumph, this week, we see a wonderful example of what can be achieved when parents stand firm beside their children.

As I thought about this idea of constancy, this week, I found myself thinking about my parents.

In particular, I found myself thinking about them at the end of their lives.

When my father died, and two years later, when my mother died, I did a lot of writing.

And as I meditated, this week, about the passages that Liz just read, I found myself revisiting some of those journals.

Those journals of love.

Those journals of loss.

So as a way to illustrate the idea of constancy, this morning, I will weave in a few asides from my journals.

*

Psalm 8 has many layers of meaning, but the part I want to focus on goes like this:

When I look at thy heavens, the work of thy fingers,

the moon and the stars which thou hast established;

what is man that thou art mindful of him,

and the son of man that thou dost care for him?

The Contemporary English Version of the Bible translates this part of Psalm 8 like this:

I often think of the heavens

your hands have made,

and of the moon and stars

you put in place.

Then I ask, “Why do you care

about us humans?

Why are you concerned

for us weaklings?”

God is big. Big enough to make stars and place them in the heaven.

We, on the other hand, are small.

Why, the psalm asks, does God bother with us?

*

In the middle of the afternoon, from behind the hiss of the oxygen mask, Dad smiled at me and asked:

“Do you remember Chiang-Mai?”

“No.” I said. “I was only two years-old when we left.”

Mom looked up from what she was reading

My father gazed out the window for a long moment. Had he forgotten what he was going to say? Mid-February flurries were pushing up against the building, making the outside world gray. Thailand seemed far away.

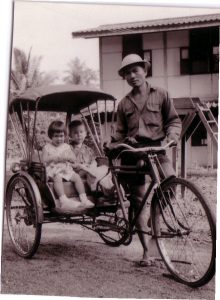

“There was Toi,” he said, “and there was Tui.”

And then, as if they had previously orchestrated a performance, Mom came in on cue: “Nai Toi, and Nai Tui. Toi was wide-shouldered and strong. He was the handyman, always called in to fix something, or do some heavy work. Tui was slight, small and he walked hunched over, you know, because he had ulcers from the hot food. He was the carpenter. The two of them were from the same village, and in the mornings they would ride in on their bicycles. Toi took a great interest in you. He would say: ‘He will crawl’ and sure enough, pretty soon you’d be crawling. He’d say ‘he will walk’ and pretty soon you’d be walking. As I said, he took a great interest in you.”

They shared a quiet laugh and Mom continued:

“I guess you’ve heard me tell this story before. I did an awful thing. One day Toi came to me and asked me for a loan, and I said to him, ‘Yes, you can have a loan, but remember that it’s not good to take loans, because you will have to pay it back.’ And, I’ll never forget, he said, ‘Yes I know, Ma’am, but I need money because Tui is sick.’”

She paused.

“I felt so bad. Toi was such a good man.”

My parents exchanged a long look.

My father smiled sadly.

“They are both gone,” he said.

*

If you followed this morning’s reading from the gospel of Matthew in the pew Bible, you would have noticed something that you might otherwise have missed.

Verse 16 through 20 of Chapter 28 happen to be the final verses of the gospel of Matthew.

After all of Christ’s ministry…

After the healing of the lepers, the driving out of demons…

After the miraculous feeding of the multitudes…

The stilling of the waters…

After all the parables and the sermons and the prayers…

After the betrayal, crucifixion and resurrection…

Still…

After all this, we have, in these final verses, an expression of doubt:

Now the eleven disciples the text says, went to Galilee, to the mountain to which Jesus had directed them. And when they saw him they worshiped him; but some doubted.

In response to this Jesus makes one final statement.

The Gospel according to Matthew concludes with these words from Jesus:

“All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, to the close of the age.”

Authority, mission, and finally, constancy.

Jesus claims that he has “All authority in heaven and on earth…”

On the basis of this authority, Jesus gives the disciples a mission: “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations…”

And finally, as if to re-assure the disciples, Jesus expresses his steadfast faithfulness to them.

His constancy:

and lo, he says I am with you always…

I am with you always…

*

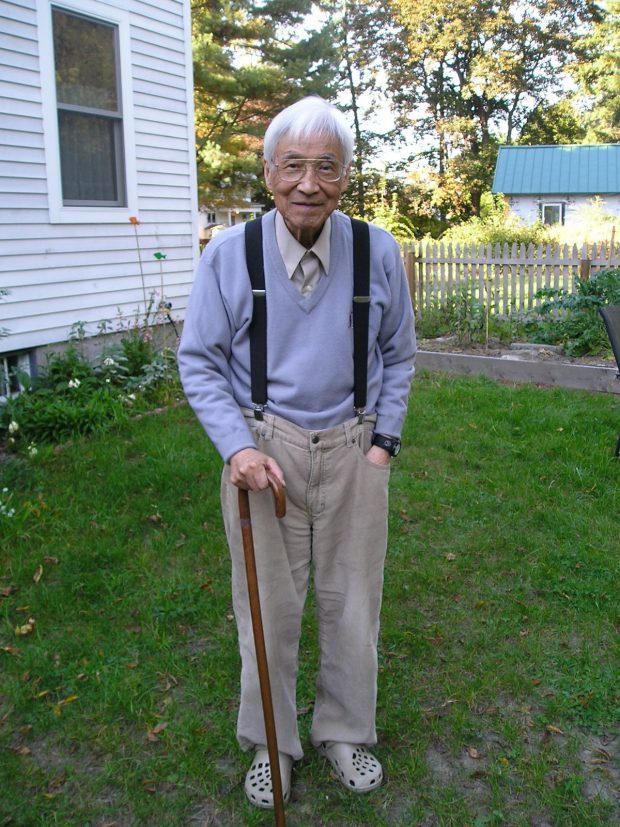

When the snow drifts still covered the yard, and a deep silence lay upon the world, my father beckoned to me and together we climbed the stairs to his office. He handed me notecard. Written in my father’s hand, were the title and author citations for three volumes: What the Gospels Meant by Garry Wills, War Made Easy by Norman Soloman, and The Diary of a Country Priest by Georges Bernanos.

It had become Dad’s habit, of late, to send me on errands to the bookstore in Amherst with such short eclectic lists. He smiled as he gave me the card:

“It’s a good sign that I am still buying books,” he said. “It means I intend to live for a while longer.”

We shared a small appreciative laugh over this kind sentiment. Dad’s oncologist had recently issued him a reprieve on the basis of a positive CT scan. The legions weren’t gone, but they weren’t having a party either. The chemo regime was put on hold – which was as good as one could want for replenishing one’s reading supply.

Whenever I was in his office, I lingered. I did not want to leave him, even though we said very little.

After a few minutes Dad spoke again. I will never forget what he said:

“I don’t know how long I will live,” he said, “but I know this. God was here before I was born. God was here during my life. God will be here after I am gone.”

*

This, I believe, brings us to the heart of my Christian faith.

Constancy.

When I think of God, I do not think of an old man with a beard sitting in the clouds surrounded by harp playing angels.

When I think of God, I do not think of some eternal being who is pulling strings up there at the top of the created order.

I do not think of someone who decides if this person should live or that person should die.

If I thought of God this way, I would have trouble being a Christian.

The existence of God is not something that troubles me.

I know that God is there, because I know that there is such thing as

a love that is long.

A love that outlasts death.

And lo, Jesus said, I am with you always…

*

I awake when it is still dark.

The dog, noticing that I am up, follows me downstairs and stands by the door.

I let her out into the chill of the November morning.

I creep past my mother’s door and up the stairs to my father’s office where I intend to try to get some work done before Silas, my youngest son, wakes and demands my attention. The light outside is beginning to change. My father’s study, with its many windows, feels like being in the sky. I look out over the neighbor’s yards. The branches of the trees, recently bare, spread upward in the cold. The dog investigates the shadows beneath the bushes. A frost holds the ground. Somewhere beyond the line of trees, a flock of geese sounds its passage. The world is cold and young.

This is my father’s time. It seems impossible that he is not here with me. Indeed, if he were to return to meet me, he would come now, while the rest of the family sleeps.

I almost feel him here.

“Its a lovely morning.”

“Yes it is.”

He is the thin old man he was shortly before he died. He smiles and puts down his book.

“How do you feel, Dad?”

“Fine.”

“Good. I’m glad.”

He walks over to me, and we stand together, looking out the window as the light of the day strengthens, filling the backyard. A red wagon lies upended where the boys left it.

“Almost all the leaves have fallen off our tree.”

“Yes.”

Amen.