Hear the question, posed to us by the Prophet Jeremiah:

For the hurt of my poor people I am hurt,

I mourn, and dismay has taken hold of me.

Is there no balm in Gilead?

Security camera footage from the restaurant on the corner shows the moment when officers J. Alexander Kueng and Thomas Lane appear at the scene. They are responding to a call about a man who has allegedly bought a pack of cigarettes with a fake 20 dollar bill. Officer Lane approaches the driver’s side of a blue SUV. Moments later, he pulls his gun.

My joy is gone, (says Jeremiah)

grief is upon me,

my heart is sick.

In America, in 2020, this is what it looks like when “the authorities” show up.

When Darnella Frazier’s phone start’s filming, there are four policemen gathered around the front driver’s side of a police car. A man is lying prone on the ground. One of the cops has his knee up against the back of the man’s neck and his face is pinned to the blacktop.

The man on the ground pleads.

I can’t breathe.

But the knee does not relent.

After almost 6 minutes, the man convulses, and goes limp. Finally, when a paramedic arrives, the cop removes his knee. Nine minutes and 29 seconds had elapsed.

Shortly after, in an ambulance, the man dies of a cardiac arrest.

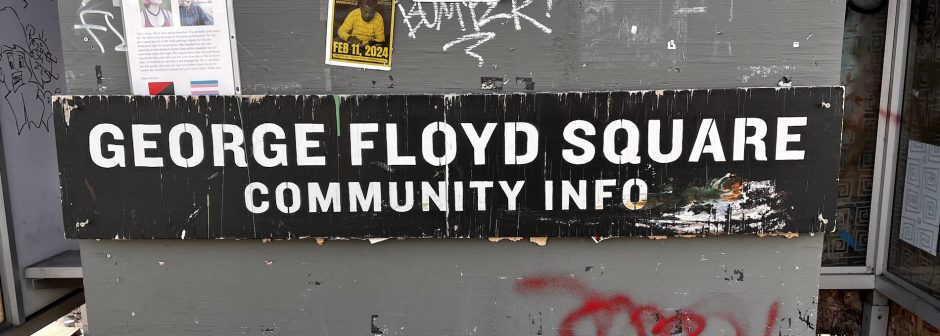

As you well know, the man’s name was George Floyd.

For the hurt of my poor people I am hurt,

I mourn, and dismay has taken hold of me.

Is there no balm in Gilead?

The brutal act sparked protests around the country and around the world. For a few weeks, it seemed like we were all united in our moral outrage. For some reason – maybe it was the pandemic – white people were also paying attention. People of all colors, ages and religions were in the streets chanting

“I can’t breathe.”

The email Chat for our church began to simmer. A sizable contingent of our congregation said that it was time to get off the sidelines. A proposal was made to put a Black Lives Matter sign on the front lawn.

It was at this moment – when the life of our country was in the grips of an awful paroxysm – that my life, and my ministry was changed forever.

It began with a text.

Mona, who was perhaps the most outspoken advocate for putting out the Black Lives Matter sign, texted me asking if I could help her gather some black and white fabric. Why buy a Black LIves Matter Banner? she asked. Let’s make one!

This suggestion set off a chain reaction in my mind.

My church has a lot of people who like to sew. This could prove to be an interesting collaborative project. My next thought was that, not just our church, but, in fact, most churches have a decent number of quilters in the pews.

Quilts!

Then I remembered the AIDS quilt.

Do you remember the AIDS quilt?

Let’s take a moment to appreciate the elegance of the AIDS quilt as an agent of change.

At the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, the stigma around AIDS was so deep that many who perished from disease were denied funerals. Until Rock Hudson came out and announced that he was dying of AIDS, most people just weren’t paying attention. Gays and Haitians, we thought. Not our problem.

It was in this context that the AIDS quilt appeared. It was a simple idea – survivors commemorated their loved ones who died of AIDS, by making a quilt in their honor. Perhaps because of its direct appeal, the idea took hold and gathered momentum.

Both the energy that inspired the AIDS quilt, and the empathic response it evoked, flowed effortlessly from the undeniable resonances that lie at the core of our human condition: our love, our loss, our hope for grace, our brokenness, and the improbable, but very real, possibility of redemption.

At its peak, the AIDS quilt included over 21 thousand panels that came from every state in the Union and 28 countries besides. When it was displayed on Washington’s National Mall, in October 1992 the quilt stretched from the base of the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial.

For the hurt of my poor people I am hurt,

I mourn, and dismay has taken hold of me.

Is there no balm in Gilead?

The AIDS quilt was activism at its most creative, and its most effective! It created improbable coalitions; communities of shared purpose. It harnessed the transformational power of symbols to quell the stigma that had been unjustly attached to the people who were suffering and dying of AIDS.

This chain reaction of ideas was exciting. I was immediately conscious that I had stumbled onto something amazing. I was not a quilter, but I had no doubt that the art form had enormous promise, not only as a change agent, but also as a way to engage the things that church is best at – the power of symbolism, the joy of shared purpose, the intention, humility and gravity of prayerfulness. There was, it occurred to me, a very good reason why people who quilt like to go to church – the artform, like our faith in Christ, is embedded in an ethos of compassion. Love is in the stitching of a quilt, and love is in the bestowing of a quilt. Quilts are made to provide warmth for someone you love!

It was later that same day, that I received an email from a non-profit that, in the wake of George Floyd’s death, was promoting the idea of police reform. In the body of that email, I found the words that Mr. Floyd spoke, as he was dying. They looked like a poem. As I read them, the awful realization came to me, that at the end of this poem, the man speaking the words would be dead. This was a poem like no other. These words, like the words of Jesus on the Cross, were a distillation of human pain, that it was impossible to look away from.

The two ideas came together.

Stitch these words into quilts. Collaborate across churches. Confront this violence with love.

The Sacred Ally Quilt Ministry.

For the hurt of my poor people I am hurt,

I mourn, and dismay has taken hold of me.

Is there no balm in Gilead?

**

The prophet Jeremiah asks a question.

Is there no balm in Gilead?

The question is asked in the midst of adversity. The Jerusalem of Jeremiah’s time is threatened by the Babylonian Empire, biding its time, like a cat about to pounce. The prophet Jeremiah believes that because many in Israel have broken God’s commandments, Jerusalem will be given into the hands of the Babylonian conquerors.

And he is not wrong.

During his lifetime, in 587 BC, Jerusalem fell to the Babylonians. Solomon’s temple was destroyed.

Is there no balm in Gilead?

Is there healing for a shattered people?

The question remained unanswered until, centuries later, on the other side of the world, it was answered. African men and women who had been kidnapped, ripped from their homes and enslaved in the Plantations of the southern United States… It was these men and women, who toiled under the lash in hot cotton fields all day, and worshiped God in secret in the depths of the night…

it was these people… the ancestors of George Floyd… who answered Jeremiah’s question.

Though they were enslaved.

Though they were beaten and whipped, raped and worked to death…

They did not say no.

They did not answer by agreeing that “There is no balm in Gilead.”

They surely could have – perhaps they should have – said no.

There is no balm in Gilead.

But they did not.

Instead, they turned the question into a proclamation:

There is a balm in Gilead

They sang…

There is a balm in Gilead (sung)

To make the wounded whole;

There is a balm in Gilead

To heal the sin-sick soul.

**

What, then, is this Balm?

What is this healing for a shattered people?

Let us turn to the eighth chapter of Matthew.

When Jesus entered Capernaum, a strange thing happened.

If the restaurant on the corner had a security camera pointed at Jesus, that day, so long ago, it might have picked up the arrival of the Roman Centurion.

“The authorities” showed up.

Uh Oh!

That can’t be good.

Israel, in the first century, was an occupied country. The Babylonians, by this time, had come and gone. The new rulers were from Rome. The appearance of a Roman centurion, then, was significant. This was a man emboldened by worldly authority.

Did he immediately draw his sword?

No.

In fact, according to Matthew, the opposite happened. The centurion “came to Jesus, appealing to him and saying, ‘Lord, my servant is lying at home paralysed, in terrible distress.’

Is this what it looks like in the gospels, when “the authorities” show up?

Apparently…

Clearly this centurion is a man who is accustomed to telling people what to do. Describing himself, the centurion says:

I say to one, “Go”, and he goes, and to another, “Come”, and he comes,

But this story is an inversion. Instead of telling Jesus what to do, the Centurion approaches with humility, asking Jesus to help his servant who is “in terrible distress.”

Do you suppose that Jesus, too, assumed that the Centurion would draw his sword? Maybe Jesus is also taken aback by this Authority, who approaches gingerly, with his hat in his hands.

I suspect Jesus and his followers probably got nervous when the authorities showed up.

But in this gospel story, all concerns of power is swept aside. The centurion does not intend to exert his will over Jesus. Though he carries a sword, it remains sheathed, because the centurion’s act is an act of love.

There is a balm in Gilead

The centurion is not asking for a favor on his own behalf. He asks on the behalf of another. And this other, is not his son or his wife. He asks on behalf of his servant, who is in terrible distress.

This story, is the direct antithesis of the story of George Floyd’s death. Mr. Floyd died because love was erased by power.

In this story, power was erased by love.

In there a balm in Gilead?

There is a Balm in Gilead.