What do we do about stories from the Bible that make us uncomfortable?

I don’t mind this story that Deb just read for us from the 16th chapter of the first book of Samuel, as long as it happens several thousand years ago, and doesn’t threaten to happen now.

In the story God orders the prophet Samuel to orchestrate the process of replacing the King of Israel.

It appears that Saul, the current King, has lost God’s favor, because the reading begins with these words, straight from God’s mouth:

“How long will you grieve over Saul? I have rejected him from being king over Israel.

Whatever ideas that the prophet Samuel himself may or may not have about Saul’s ability to be King over Israel seems to be beside the point.

Fill your horn with oil and set out;

God says to Samuel

I will send you to Jesse the Bethlehemite, for I have provided for myself a king among his sons.”

“I have provided for myself…”

This is not exactly a democracy is it? God is not only ignoring Samuel’s opinion – the people of Israel themselves are not even considered in the decision-making process. Since it concerns the wielding of power, Kingship seems to be the sole concern of God…

“I have provided for myself a King…”

The way this story is told, the decision making process seems to be entirely in the hands of God. God is the one making the decisions, and since God is God, we – the lowly mortals – are expected to accept everything without question.

God wields power. We submit to it. That, at least, is the worldview that is working not-too-far under the surface of this story .

But if this happened today, I wouldn’t be questioning God’s authority. The person I would be very concerned about, would be the Prophet Samuel.

When we hear this story, we willingly accept the way the narrative develops because we are inside Samuel’s head, and we accept the notion that Samuel is in direct conversation with God. Indeed the internal logic of this story depends upon this assumption – that Samuel’s actions are directly guided by God – it’s almost like God is a voice in Samuel’s head, talking to him as the events of the story unfolds.

But if we lived in the days of Saul, and we were watching all of these events unfold, I bet we would be frightened of Samuel’s power. Samuel would seem less to us like an obedient servant of God, and more like a King-maker.

How could we be confident that Samuel really knew the will of God? Because he said so?

I once met a person who made this claim about himself. This person – no one you know – said that he was certain that the words that he spoke and the beliefs that he held were true beyond any doubt, and when I asked him how he knew this to be the case, he stated quite calmly that it was because God spoke to him and told him so.

As a minister, I was a little put out by this. I spend my life using all the tools I can muster (interpretation, poetry, meditation, writing, prayer, and discernment) to try to fathom the mystery of God, and this guy just has conversations with God, like he has some kind of Divine speed dial. No discomfort, no beauty, no challenge, no poetry, just a straight talking God who agrees with everything he thinks.

How convenient to have such a God in your backpocket. A God who is always there to give you the universe’s best thumbs up.

“That thing you think — 👍🏼– right you are! Well done, Junior!”

When I gently challenged this man’s assertion that his truth came directly from God, he smiled knowingly and said that he fully expected people not to believe him. Jeremiah and Isaiah spoke for God too, didn’t they? None of the little people believed them either. He knew how they felt! .

What was I to say to that?

It felt like that moment in the playground when you shout “Am not!” and the other kid yells “Am so!” and you go back and forth like that without getting anywhere.

This is one of the painful ironies that is forever present in every religious tradition. Lao Tsu, the founding philosopher of the Chinese religion of Taoism, was onto something when he said that: “The Way that can be spoken is not the true way.”

If a person claims to speak on behalf of God, more than likely they are really speaking on behalf of their own interests – their own desire for power.

Theocracies – states like present day Yemen and Iran who base their system of government on religious doctrine – are universally feared as the most repressive governments in the world because their power cannot be challenged. People who voices of dissent are immediately dismissed as heretics because the clerics who hold power have recourse to the same God who lived in my former acquaintance’s backpocket – the God who conveniently agrees and ruthlessly enforces, everything they demand.

As people of faith, we live, forever, on the precipice of this danger. If we claim to know God’s will, we flirt with a great danger, but at the same time, if we don’t at least try to figure out what God might expect of us, we end up living superficial, meaningless lives – lives that do not peek into the great depth that mysteriously holds us in its sway.

*

Enter, now, the fascinating second part of this King-making story.

We are still in the Prophet Samuel’s head, and he is still in the process of making a King, but it is not going as he expected.

He has been told that this new king will be a son of Jesse, and so he gathers Jesse and all his sons together. Each of Jesse’s son’s is presented to Samuel, from oldest to youngest. When the first one, Eliab, is brought before him, Samuel looks upon the tall, gracious and wonderfully strapping lad and is filled great pleasure. He says to himself:

“Surely God’s anointed is now before the Lord.”

But no. God, who we have agreed (for the sake of this story) is speaking directly into Samuel’s ear, does not share the prophet’s good impression of Eliab:

The Lord said to Samuel, “Do not look on his appearance or on the height of his stature, because I have rejected him…

This is a crucial moment.

God disagrees with Samuel.

Speaking in the third person about Godself, God says:

“…the Lord does not see as mortals see; they look on the outward appearance, but the Lord looks on the heart.”

Ahhh.. The Bible takes away and the Bible gives back again!

Just when you think that the text is setting up the most troubling, anti-democratic vision of theocratic governance… the Bible undermines such a suggestion by reaffirming that, essentially, God is still beyond us – still a mystery that requires us to act, not with the hubris of a King-maker, but with the humility of a seeker.

An arbiter of power – one who is in the very act of bestowing kingship – must not labor under the misconception that it is sufficient to see how mortals see. It is not! Because we see partially. We try to peer into the depths, to glimpse what is there, but we remain subject to our superficial prejudices.

This God who looks at the heart, is not a backpocket God.

This is not a God who is eager to please those in power.

Such a God is a God who is made in our image.

No.

This is a God in whose image we are fearfully and wonderfully made – an image (though it is our own) that we will never fully comprehend.

*

When I read this part of this morning’s passage – the part in which God looks at the heart I was reminded of time, many years ago, while I was studying Biblical Hebrew and my beloved professor and mentor, Dr. Phyllis Trible, pointed out the word “nephesh.”

I have printed the Hebrew word on the cover of today’s bulletin.

The word Nephesh is significant because it means something that we cannot say in English. The only way that we can translate this word is by using four words: Mind, Body, Heart, and Soul.

English requires us to think of mind as one thing, body as another, heart and something else, and soul as none of the above.

In Biblical Hebrew, however, you can refer to all of those ideas with one word.

One concept.

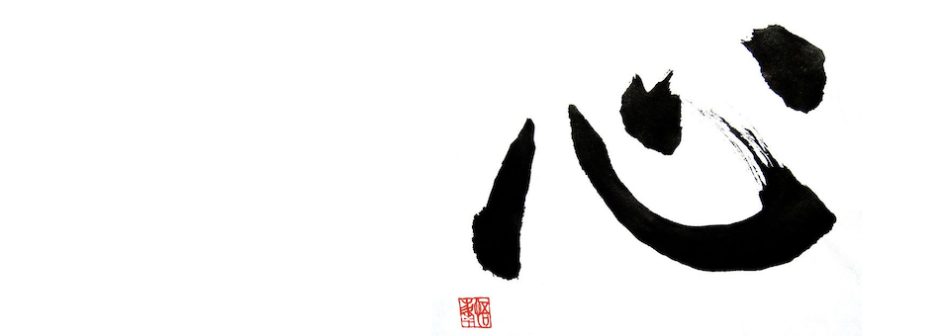

I recently learned that Japanese also has a word for great cumulative sense of being – in Japanese the word is Kokoro.

I have also printed the Japanese character on the cover of today’s bulletin.

I want to conclude with this idea – that this linguistic nuance is suggestive of the spiritual insufficiency that is pointed out in today’s scripture.

We humans suffer the spiritual insufficiency of seeing each other partially – in parts. We see a mind,

Perhaps we see a heart,

Sometimes we recognize a body,

Perhaps we sense a soul.

But it is God who know our Nephesh.

It is God who knows our Kokoro.

Amen.