In most of the post-resurrection stories, Jesus has a problem that he must overcome.

He must somehow prove to his disciples that he is real – that he is alive – and that he is not a ghost.

If he was a ghost – he would be an explainable thing – an it – something to be dismissed.

But as a resurrected, living man, Christ is something extraordinary – something to be marveled at.

Something sacred.

In one resurrection story he eats a piece of fish. In another, he breaks bread.

In this story – the one we have just heard, he does something quite strange.

He allows his disciples to touch the wounds – the evidence that remains of his traumatic death on the cross.

**

There is a problem that has been plaguing me for some time too. I suspect that old Doubting Thomas may be able to help me figure it out.

I hope so.

The problem has to do with the Sacred Ally Quilt Ministry.

You may recall that when I first had the idea to make quilts that memorialize the dying words of George Floyd, I called it the Sacred Ally Quilt Project. Back in May of 2020 – my stated purpose was to show our black and brown brothers and sisters that there is a whole demographic of people here in New Hampshire who really want to be allies, but don’t know how.

In my proposal to the churches of New Hampshire I wrote:

…the nation is reeling. George Floyd — yet another black man has been brutally killed in police custody. Pleading for his life, he was pinned to the ground, where he suffocated and died. Our nation, already traumatized by a pandemic, has descended into deep trauma, riots, anger, crackdown, curfew. Racism is deeply entrenched in our country.

How do we address this huge problem? How do we heal?

One way to begin is to prove that racism is not the only reality. There is, for example, a huge demographic of progressive people who feel called by Christ to demonstrate that we are allies for our black and brown brothers and sisters. How can we meaningfully harness this energy?

My answer to the question “How can we harness this energy?” was the quilts.

Make quilts – symbols of love – to prove that there is an alternative to racism, and that alternative is love.

I still think my idea was a good one. By engaging, over a long period of time, in the process of making these quilts, we, as a church – indeed a group of nine churches – would prove that racism is not the only reality. These good Christian communities would willfully and intentionally do the work to make this statement true.

And we did this! We made the quilts.

And the making of the quilts was just the first stage of the life of the quilts. Once they were gathered together, it became clear to us that we had created a powerful antiracism tool. The “project” was transformed (largely through the prophetic vision of Dr. Harriet Ward) into a “ministry” and the exhibit began traveling around New Hampshire and beyond.

Two years later, far from losing steam, the quilts are just becoming more and more in demand from churches and institutions all over the United States. Everywhere they go, they create important transformative discussions about racism and racialized violence.

We did this – you and I, and Dr. Ward and Kathy Blair and quilters from nine other UCC churches – we created a powerful antiracism ministry.

Everywhere they go, the quilts insist that violence is not the answer –

Everywhere they go, the quilts insist that God’s love is real.

Everywhere they go, the quilts insist that “racism is not the only reality.”

All of this sounds good.

But I started my sermon saying that there is a problem that has been plaguing me.

So what is the problem?

The problem may not be obvious to you.

It was not obvious to me, until it was pointed out to me.

But it is obvious to almost any Black person who hears about the Sacred Ally Quilt Ministry.

The problem is the word “Ally.”

The word “Ally?”

What could be wrong with the word “Ally?”

When we proclaim, for example, to be Ukraine’s ally in their struggle against Russia, we are committing to helping Ukraine face their problem – the threat presented to them by the Russian military.

Isn’t this a good thing?

Sticking up for the underdog – isn’t that the moral thing to do?

But, as Black theologians and activists correctly point out, the idea of white people allying themselves with black people against racism is a notion that is rife with painful ironies.

The first irony, of course, is the idea that Black people somehow need white people to come and save them from racism. This makes it sound like racism is a problem that has its origins among Black people.

And this, of course, is the farthest thing from the truth.

Racism is not a black people’s problem.

The sour, curdled roots from which racism springs, is the sin of white supremacy.

Racism is a white people’s problem.

So when white people show up to be helpful, it doesn’t always feel genuine.

Because sometimes – often – it is NOT.

The danger – the very real danger of the term “Ally” is that it white people can use it as an elaborate form of denial.

When I proclaim that “I am an Ally,” I assure myself that I am absolved of the sin of white supremacy. How convenient! But this label, this credential, this smug self-assertion, cannot support such a great trick. Ironically, this cheap absolution does more to perpetuate white supremacy than dismantle it because my proclamation makes no real difference to anyone but myself. It is a performance that I use to congratulate myself, and while I’m busy feeling good about myself, the intransigent, cruel realities of racism continue to move unchecked through our culture.

So when black people see the word “Ally” in “Sacred Ally Quilt Ministry” they probably don’t receive the message that I originally intended – the message that “racism is not the only reality” and that there is “a huge demographic of progressive people who feel called by Christ to demonstrate that we are allies.”

For many Black folks that I have encountered on my travels with the quilts, the term “ally” is met with suspicion. It is especially suspicious when it is seen to be claimed rather than bestowed.

We think of “ally” as an identity that we can claim, but Black people consider it a kind conditional possibility.

You think you’re an Ally?

We’ll see about that. It remains to be seen.

**

Let us turn now to the story of Doubting Thomas – the post-resurrection story from the Gospel of John that Vicki read for us earlier.

This tale is generally told as a kind of allegory about the nature of faith. In this traditional interpretation, Thomas is understood to be a person whose faith is not as great – Jesus even says so. In order for Thomas to give his belief, he must see – or rather, touch – the evidence.

This morning, though, I find myself less interested in Thomas’ faith. I am more interested in the wounds.

In almost every post-resurrection story Jesus does something to demonstrate to his disciples that he is actually alive, and not a ghost. On a few occasions, he eats something in order to prove that he is not a ghost.

In this story he visits the disciples twice, and on both occasions, he proves his identity – and his physical reality – by allowing his disciples to touch his wounds.

Thomas, who was not present for the first visit, does not believe it was Jesus. He will only believe, he says, if he too gets to touch Jesus’ wounds.

The wounds…

In this story all of the disciples – not just Thomas – are interested in those wounds – the holes in his hands left by the nails, and the cut in his side left by a Roman spear.

These are not just wounds. They are mortal wounds. They are evidence of a murder.

They are evidence that God knows what it is like to suffer and die as only a human can suffer and die.

The incarnation of God has not simply come to live among us. The incarnation of God has become completely human, by suffering completely. The wounds prove it.

This is different from a normal story about human suffering. In every other story, humans inflict pain, suffering and death, upon other humans. In this story, God is also present. Humans inflict pain, suffering and death on God.

The wounds are the evidence of human suffering. The wounds are also the evidence of God’s suffering.

God is present.

There is no credential here – no label – no smug self assertion.

God is fully present.

The mortal wounds show this.

**

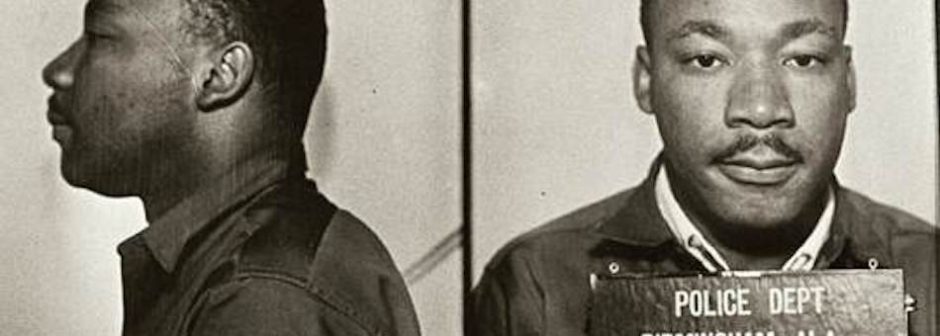

On this day, 60 years ago – April 16th 1963 – The Reverend Dr, Martin Luther King Jr., finished writing the historic document that has become known as the Letter from Birmingham Jail. I have marked this occasion by placing two quotes from this extraordinary letter in the bulletin.

When, in the quote on the back of the bulletin, Dr. King bemoans the “white moderate” who “is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice…” one hears, in his words, the dangers inherent in the word “ally.”

In the quote that I have included on the inside of the bulletin, Dr. King paraphrases the Jewish theologian Martin Buber. Buber is famous for his book I and Thou in which he suggests that the great sin of humanity is our ability to see ourselves as I, and others as “it.” When we see others as “it” – that is, less than human, we sin against God. When we bring God into our relationships – when God is present – then we relate to others as “thou.”

When God came to us and we touched God’s wounds, God was present. That was a thou moment.

**

My great hope – the hope that I am trying to live into – is the hope that the adjective “Sacred” modifies the meaning of the word “ally” in a meaningful way.

When we named the Quilt ministry – we did not name it the “Ally Quilt Ministry”

We named it the “Sacred Ally Quilt Ministry.”

When we modify the word “Ally” with the adjective “Sacred” we insist that God is present.

We insist that this “ally” is not about credentials, not about labels, not about smug self-congratulation.

In order to be “sacred” this assertion of “allyship” must involve God.

God must be part of the relationship.

God – the God who is willing to be mortally wounded – must be present.

I admit to you that I am still in the process of trying to work this out – what it means to bring God into my relationship with those that have been the victims of the sins of our history.

All I know is that it is not enough for me to have good intentions.

Allyship – sacred allyship – is an ongoing process of discovery. Discovery of the wounds that have been inflicted.

Discovery of God’s capacity to do the mortally hard work of healing.